Published 18.12.2020

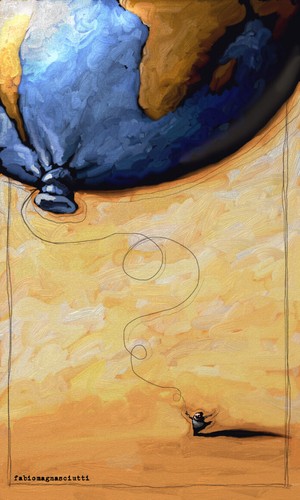

Illustrations by Fabio Magnasciutti and Pixabay

Click for Norwegian

The Arts in the Ecosystem

Everything we love is transient, fleeting, temporary

by Erland Kiøsterud

A human body digests dead animals or plants and then goes to bed and reproduces; a lake exchanges death and living matter with itself and its surroundings; an empire occupies new land and initiates oil drilling: Common to these three events is that we are dealing with an ecosystem interacting with surrounding ecosystems. The world consists of such, small and large ecosystems.

Ecosystems are constantly changing, they are changing to withstand change – to sustain themselves. It’s natural. We humans, just as naturally, want to stabilize ecosystems to have good, predictable lives. The more man takes control of the ecosystem’s nature in order to have predictable lives, the greater the consequences for man when the ecosystem breaks free from our temporary control to release energy and seek new stability. Man himself is nature. How are we to understand this?

The question of whether it is we who speak into nature, or whether it is nature that speaks in us when we use technology to break ground and build factories – when we intervene and change nature, form cultures and create art – has not been answered. It will not be answered here either, but remain the open, unpredictable space in which this essay is written.

To the question who – or what – speaks, belongs the question of language: For with what images, with what symbols, and with what grammar does man describe the ecosystem when he presents its way of being? With what conscious or unconscious linguistic structures and tools do we intervene in nature; our own nature and the nature that surrounds us?

Do I have insight into which lives I exclude with that form, that work of art, or with the essay I am now in the process of establishing? Do I know enough about the expulsion mechanisms that are built into my form formation – about the deep structures in the expression I use – and which are hidden from me because I am a part of it? Am I a liberator or an oppressor? Am I increasing or decreasing the silence in the world? Am I driven, even in my desire for change, by forces I do not see

The subject of this essay is: What does it mean for man to move from an anthropocentric – human-centered – way of being in the world, to an ecocentric way of being in the world. What does it mean, theoretically and practically, for the engineer, for the economist, and for the artist (the author, the musician, the visual artist, and so on) to go from an understanding of man as the goal and meaning of all things to understanding the preservation of the ecosystem as the goal of all things and meaning? What are we doing, and what is happening to us now that we are changing our way of thinking and behaving more radically than we have probably done since the Neolithic revolution? Who speaks, with what language, to whom – to what in the ecosystem?

The subject of this essay is: What does it mean for man to move from an anthropocentric – human-centered – way of being in the world, to an ecocentric way of being in the world. What does it mean, theoretically and practically, for the engineer, for the economist, and for the artist (the author, the musician, the visual artist, and so on) to go from an understanding of man as the goal and meaning of all things to understanding the preservation of the ecosystem as the goal of all things and meaning? What are we doing, and what is happening to us now that we are changing our way of thinking and behaving more radically than we have probably done since the Neolithic revolution? Who speaks, with what language, to whom – to what in the ecosystem?

In the midst of a high-tech culture that, like all cultures, sees itself as the ultimate in history, a new and perhaps more intelligent way of organizing itself in the world is emerging. Questions are asked about what technology, economics, and art in general are, questions are asked about the way technology, economics and art behave in the ecosystem.

All over the world, artists are trying to understand what it means to create art in the ecosystem. The self-understanding of art is reformulated here and now. It is not a question of art in the service of the ecosystem or of whether art should be relational or intervening and so on, but what should we understand as art at all? Does the author, musician, and visual artist leave the old identity behind and create a completely new one? If so, where does the artist get the new language from, and with what – with whom does she communicate? With her new – or old – me? Does this ‘self’ exist? Or does she communicate with the ecosystem? Which ecosystem?

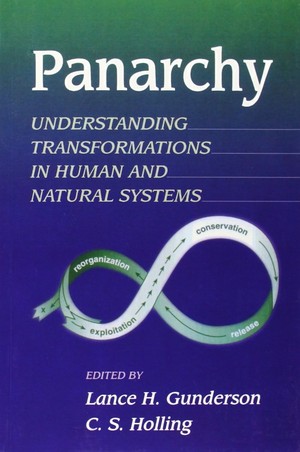

In Panarchy: Understanding Transformations in Human and Natural Systems (Island Press, 2002), Lance C. Gunderson and co-editor CS Holling describe the behavior of the ecosystem. They try to portray it – not the way we humans want it to be, in harmony and balance – but the way it actually unfolds, whether the ecosystem is a colony of viruses, banana flies, a business, life in a lake, a forest or a society.

In Panarchy: Understanding Transformations in Human and Natural Systems (Island Press, 2002), Lance C. Gunderson and co-editor CS Holling describe the behavior of the ecosystem. They try to portray it – not the way we humans want it to be, in harmony and balance – but the way it actually unfolds, whether the ecosystem is a colony of viruses, banana flies, a business, life in a lake, a forest or a society.

In short, and very generally, any ecosystem occurs in wild and robust growth (depending on the way of life, growth can take hours or thousands of years) before it stabilizes. In this stabilizing and more specialized phase, the ecosystem streamlines energy consumption to best sustain itself. The streamlining makes the system vulnerable to influences. Small changes in the form of external or internal events that may have built up over time – such as climate change or increased salinity in the groundwater, you often do not see it until after they have occurred – may in this energy-saving phase cause the ecosystem to suddenly pass thresholds and collapse. What happens is that the ecosystem releases energy to reorganize – dissolve, transform, or innovate – in order to remain an ecosystem. In this liberating phase, creativity and new formations on a micro level may produce big consequences on a macro level – something new may arise. But incorrectly «handled», a toxic algae bloom or a dictatorship may just as easily see the light of day as a new nesting bird species or an ecological way of life.

The instructive thing about Gunderson’s and Holling’s research is that they try to avoid transferring the human need for harmony and stability to nature. Instead, they try to describe the ecosystem as it actually behaves in the short and long term, without meaning and ethics, without thinking about humans or animals. This includes not only regional ecosystems and their local biotopes, but all ecosystems, from the individual microorganism to the major global ecosystems – including the technological, political, economic, and knowledge ecosystems and their origins, mutual influence, collapse, and innovation. We are in a world of continuous change and transformation where, for us, seemingly insignificant factors, on small or large scales in the system, that have grown over time, suddenly may create unforeseen events and completely transform the ecosystem we inhabit and depend on.

In Beyond Nature and Culture (University of Chicago Press, 2014), the anthropologist Philippe Descola examines the different ways in which man throughout history has adapted to the ecosystem. Of the stories that humans have adapted to the ecosystem with (and which are often found in a mixture), he finds four main forms:

In Beyond Nature and Culture (University of Chicago Press, 2014), the anthropologist Philippe Descola examines the different ways in which man throughout history has adapted to the ecosystem. Of the stories that humans have adapted to the ecosystem with (and which are often found in a mixture), he finds four main forms:

1 : In an animistic society, I and the animals around me have different external forms, but inside we are equal. We share, eat, recycle, and transform the same plant and animal organisms (including each other). We share the spirit of life – that in nature that gives life – we see that one can transform into the other, we are part of the same, each species has its cultures, knowledge, customs, and objects they sustain life with, such as housing and food. We do not overtax resources, we respect each other’s boundaries.

2 : Whereas an animist, I see myself in all living things, I connect as a totemist to one particular plant, natural formation, or an animal that I lead the whole group – or clan – history back to. In my origin story, I maintain a binding moral and physical continuity to the origin, the nature I come from, and like the animist (but here there are exceptions) I make sure not to overtax nature. In the dream time, I relive, with Aborigines as an example, the creation of my world – and as I move through the landscape, I go through the stories of the landscape and the ancestors. We share substance: Society, nature and my histories are one and the same thing. I live as the animist «beyond nature and culture», beyond the distinction between nature and culture.

3 : I do the same when I live in what Descola describes as an analog society. There everything is connected – nature and people, objects and souls, microcosm and microcosm – together in the form of correspondences and gradations, as it was believed in the Middle Ages that human blood vessels corresponded to landscape rivers, bones corresponded to mountains, or where I with my amulet around my neck in Mexico can have direct contact with the spirits. A buckhorn in the ground at Vidaråsen in Vestfold can thus stimulate the growth forces. Everything has its place, its continuity, and coherence in this strange universe which under fortunate circumstances can be read and influenced. The world is one big network of meaning. The downside: Since everything is connected to everything, whoever gains control of this network of meaning can also control society.

4 : According to Descola, scientific rationalism constitutes the fourth main narrative with which man has aligned himself in the ecosystem. As a rationalist, unlike in the other three main forms, I create a marked distinction between myself and nature – or more specifically with the animals: I can think, the animals can not. My ability to abstract enables me to put myself outside, or rather above nature: By systematizing and classifying the world around me, by taking parts of it out of context and turning nature and myself into analyzable objects, I can make models and with my neutral, analytical gaze intervene in and transform nature – as if it were a lump of clay I can shape in my own image at my own discretion, like an almighty God, from without.

As a rationalist, I believe I am able to control organic life, I create an equivalent to it, the value of money so that everything can be traded. He who controls the flow of money and desire in this society controls the world. In my special position, at the top of the food and knowledge pyramid, I as a rationalist am convinced that in the long run, I will do better than the animals. That is far from certain. By erasing my biological origin, separating myself from nature, objectifying it, and instrumentalizing my relationship with the outside world, I may have given up the tools I need to survive in the long run, writes Descola. He concludes this incomparable work, which is not without blemishes, with the following, freely translated: that it must be allowed to hope that with a listening and respectful commitment we will be able to prevent a future point of «no return», and the extermination of the human race, to avoid that our passivity won’t leave the cosmos a nature shorn of its storytellers – only because they fatally failed in giving nature an adequate expression.

In From Being to Living, a Euro-Chinese lexicon of thought (Sage Publications, 2020), the philosopher and sinologist Françoise Jullien draws the lines where Chinese and European understanding of nature diverge. He shows how Europe has developed a transcendent understanding of nature by looking at nature from the outside, through concepts, as the abstract «concept of being». For thousands of years, completely independent of Europe, China has developed an immanent understanding of nature by observing nature from within, by living in it and with it. In classical Chinese knowledge tradition, nature is what happens. Nature, the world, is neither created by any spirit nor external god, it creates itself, every day, all the time, without any external or internal cause, power or will. Humans, plants, and animals are an inseparable part of nature, they are neither above nor below it, they sense and live in it, here and now, while it changes.

In From Being to Living, a Euro-Chinese lexicon of thought (Sage Publications, 2020), the philosopher and sinologist Françoise Jullien draws the lines where Chinese and European understanding of nature diverge. He shows how Europe has developed a transcendent understanding of nature by looking at nature from the outside, through concepts, as the abstract «concept of being». For thousands of years, completely independent of Europe, China has developed an immanent understanding of nature by observing nature from within, by living in it and with it. In classical Chinese knowledge tradition, nature is what happens. Nature, the world, is neither created by any spirit nor external god, it creates itself, every day, all the time, without any external or internal cause, power or will. Humans, plants, and animals are an inseparable part of nature, they are neither above nor below it, they sense and live in it, here and now, while it changes.

Classical Chinese understanding of nature is about preparing to live well in and with nature as it changes. Cold gets hot and hot gets cold, life becomes dead and death becomes life, the river floods and it settles down, drought and bad years come and go. The art is to understand the change in its germ before the change becomes known; to be able to see that something is about to end long before it is at height; to see that something is in the making, in its beginning, long before it begins, to be able to influence and regulate the events, and to adapt to the changes, before they are there. The art is to understand nature’s complex processes as they go on.Every event, every situation is new: The wise, the engineer, the economist, the artist, does not position himself with his abstractions above nature and impose his preconceived understanding on it, but listens, once again, with his experience, to what now happens, to be able to interact. The subject (the understanding of an isolated subject does not exist in classical Chinese) is not created by being above the event, nature, but by emptying itself and becoming a part of it.

Vigilance, presence, and humility are the keywords. Awake and present in the silent transformations that take place at all times, man is a listening part of nature, a compassionate part of the world. Desire, hubris, and absolutes give blindness and pain, listening to presence hope for relief.

Living in understanding – and interaction – with the ecosystem, as presented here, is not a solution to the «problem of life». It raises more problems than it solves and in the first instance probably also creates more pain. But is that perhaps the only way we can preserve our livelihood, the ecosystem of nature, the only way we can grow as human beings? And find a reason for our passions.

The icons of the Middle Ages depict the God of Christians, the creator, in an inverted perspective. It is not we, the viewer, who sees the depicted creator, but the creator who sees us: We are seen. In the Renaissance, the perspective is turned 180 degrees. From being the one who is seen by God, the Renaissance artist takes God’s place to be the one who sees and rules the world. Far into the 20th century, this subject, as dominant as it is sovereign, rises up in European art, only to gradually weaken. Ongoing migration into the big cities, capitalization of the sphere of life, mass production of identity-leveling consumer goods, totalizing world wars, identity-crushing genocides – and modern computer technology with de-personifying consequences – the European subject slowly lose body and contour in art. It is gradually erased, without a marked, new subject comes in its place. Maybe it is something to resort to.

In the ecosystem, man is neither a supernatural metaphysical being seen by his creator nor a dominant colonialist with a God-given right to rule over nature. In the ecosystem, man is in nature, he is a part of nature, on which he is completely dependent. Man will never be able to master nature, at best he will be able to hope to understand it in order to adapt to it.

Roy Rappaport describes in Ritual and Religion in the Making of Humanity (Cambridge University Press, 2013) how man – in a world that in principle will always be without meaning – constructs meaning through religion and rituals. This in turn gives rise to conventions for behavior – for how we relate to each other and the world around us. His concrete example is isolated tribes in Papua New Guinea and their ingenious religion generated to regulate the wild pig population and grass growth in the region. At regular intervals, through rituals, society restores the balance – and meaning – between grass growth, humans and pig populations. He shows how a society can create meaning, make laws and regulate behavior in interaction with the surrounding nature, in interaction with the ecosystem of which it is a part.

Roy Rappaport describes in Ritual and Religion in the Making of Humanity (Cambridge University Press, 2013) how man – in a world that in principle will always be without meaning – constructs meaning through religion and rituals. This in turn gives rise to conventions for behavior – for how we relate to each other and the world around us. His concrete example is isolated tribes in Papua New Guinea and their ingenious religion generated to regulate the wild pig population and grass growth in the region. At regular intervals, through rituals, society restores the balance – and meaning – between grass growth, humans and pig populations. He shows how a society can create meaning, make laws and regulate behavior in interaction with the surrounding nature, in interaction with the ecosystem of which it is a part.

Our culture and our laws have not sprung from interaction with nature, they have sprung from pure predation on nature. Western case law is implemented in a people-centered manner. In Christian ethics, in Roman law – in the legal conception of the Renaissance, the bourgeois-industrial revolution, and the last century – man, with few exceptions, is at the absolute center of the legal understanding. In an ecocentric society, the conservation of the ecosystem as a whole will be at the center of culture and legislation. It is possible to imagine that engineers, economists, and artists in an ecocentric society will form practices and poetry to protect biotopes, habitats, rivers, lakes, soils, oceans, and commons, and where the engineer, economist, and artist, who also is changing, innovating, like nature itself, and preserving, like nature itself.

The road from a human-centered to an ecocentric way of life is, after all, probably a struggle against man’s anxiety for death – his urge to dominate. In Autobiography, Ecology, and the Well-Placed Self (Peter Lang Publishing, 2011) Nathan Straight – and the authors he analyzes – disguise the American myths of crossing borders and heading west to create a free and happy life on the prairie. Behind the myths of the Free, Wild West lies the murder of indigenous peoples, the enclosure of plundered property, the ditching, drying out, and use of insecticides hand in hand with the uninterrupted oppression of women in an extremely violent, masculine, fear-based, and phallus-centered universe. The liberation of women and of nature is in America, as in the rest of the world, a great and long-term decolonization work. The transition from a people-centered to an ecocentric society is also about becoming fewer. Probably man must give large areas back to the plants and animals, should the ecosystem of the earth have hope of getting some of the health back.

The road from a human-centered to an ecocentric way of life is, after all, probably a struggle against man’s anxiety for death – his urge to dominate. In Autobiography, Ecology, and the Well-Placed Self (Peter Lang Publishing, 2011) Nathan Straight – and the authors he analyzes – disguise the American myths of crossing borders and heading west to create a free and happy life on the prairie. Behind the myths of the Free, Wild West lies the murder of indigenous peoples, the enclosure of plundered property, the ditching, drying out, and use of insecticides hand in hand with the uninterrupted oppression of women in an extremely violent, masculine, fear-based, and phallus-centered universe. The liberation of women and of nature is in America, as in the rest of the world, a great and long-term decolonization work. The transition from a people-centered to an ecocentric society is also about becoming fewer. Probably man must give large areas back to the plants and animals, should the ecosystem of the earth have hope of getting some of the health back.

Leonardo da Vinci observed how much easier it is to cross a straight river with a canoe at an angle – downstream – than to spend a lot of energy and risk your life by going up against the forces of nature – and crossing the river across the countercurrent. François Jullien adds how much more beautiful it is to cultivate intimacy and the presence of the loved one than the abstract and totalizing love. Nothing can be owned. Everything is changing. Everything is in process. We are part of the nature that is changing. Life, just like everything we love, is transient, fleeting, temporary. In this lies a germ of deep understanding of beauty.

It is demanding to relinquish power and dominion – to abandon the illusion of being at the top of the pyramid of knowledge and industry. In the ecosystem, what is at the top, the next day may be at the bottom. Our culture does not know much about perceiving and expressing life, the fragile, the transient, the non-victorious, the tender, with cracks, bursts, with traces of time in, to show the time, the changes, what is created and that which ends – to be a sensitive, perceiving part of nature, a humble interlocutor in the ecosystem.

With their aggressive, partly inflated subjects, Western technologists, economists and artists have for centuries seen themselves as above nature, defined it in their own image and plundered it. Leaving this position, creating art listening in and with nature, including our own fragile nature, is perhaps still easier than we think?

Maybe there is no more than one decisive step to the side that is needed to open eyes, nose, ears, and hands to what is here, now, everywhere, in us and around us, in the walls and the trees, the floor and the forest floor, the car and the pool of poison, in the neighbor and in ourselves, in the meal and the love.

Maybe it’s just a farewell to an immature and death-ridden culture that is needed to accept the realities of life, its ephemerality, its fundamental silence and a changing nature – to understand ourselves as part of what lives; to let us be spoken to by the one who has no speech, and act and create in that world.

It is our self-understanding that is at stake today. To leave the illusion that nature exists for us, and instead understand ourselves as an interwoven, listening part of nature – this is ultimately a question of education, of refinement and sensitivity, of maturity.

Return to front page

Essays av Kiøsterud

Kunsten i økosystemet Ny Tid

Å leve i økosystemet Jorden Ny Tid

Hva er skjønnhet? Klassekampen

Agamben og avståelsens etikk Ny Tid

Polemikker av Kiøsterud

Vi bor fremdeles i feil fortelling Morgenbladet

Hvem snakker til hvem – fra hvor – i økosystemet? Morgenbladet

Menneskedyrets blinde flekk Morgenbladet

Dyrets blikk og vårt blikk Klassekampen

En av verdens første rapporterte miljøforbrytelser Klassekampen

Etikk uten Gud Vårt land

Kunsten å forstå en terrorist Klassekampen

Den største forbrytelsen Klassekampen

Intervjuer med Kiøsterud

Mental helse og retten til skjønnhet Billedkunst

Det danna menneskedyret DAG OG TID

Portrettsamtale med Kiøsterud, 2020 Vimeo video, 27min.

Vår kollektive schizofreni Harvest

Menneske og dyr i posthumanismen NRK radio

Lenker til Kiøsterud

Omtale

Tidligere anmeldelser og pressemeldinger